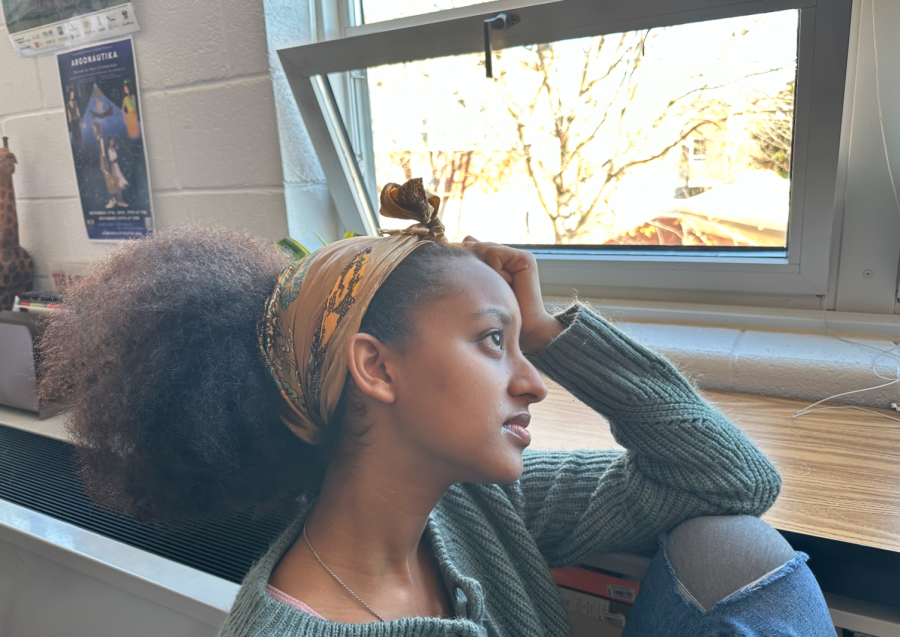

Two years ago, freshman Anna Smith, took her last stroke and grabbed the pool wall to finish up her challenging, 4 a.m. swim practice. After swimming competitively for a few years, that morning wasn’t anything she could not handle. But, as she lifted her head above the surface of the water, she was suddenly overcome with intense chest pains and could not breathe. She had been suffering from a bad cough for a couple of weeks and had asthma, so she quickly jumped out of the water to take a puff of her inhaler. But almost a full year later, Smith’s chest pain was still there…and no one had an explanation as to why.

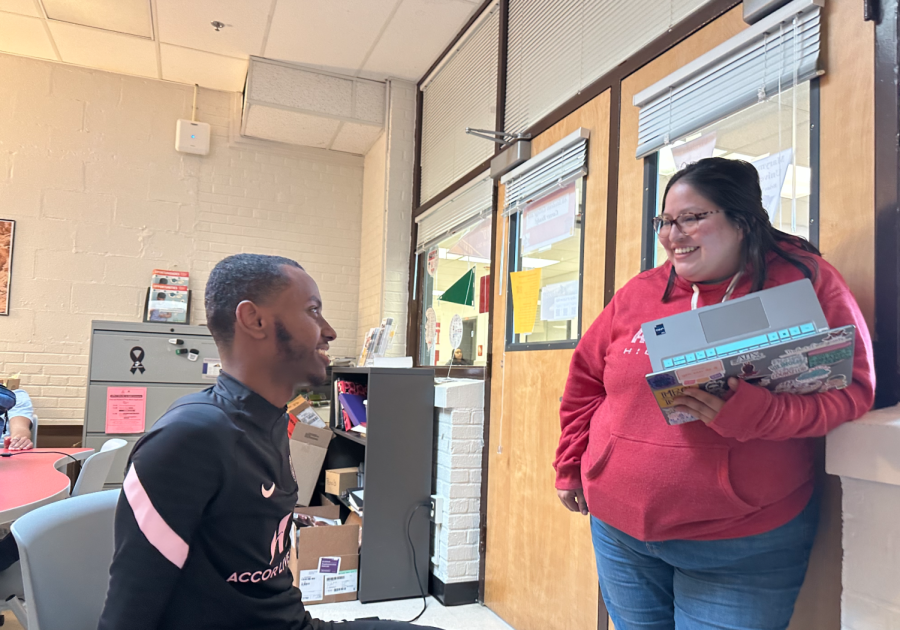

“Well I started swimming in the first grade,” said Smith, now a junior. “I really started to get faster around the third grade and began morning practices in seventh grade.” Morning practices in the swimming world equate to competing on a travel team in other sports like soccer and basketball; the level of training and coaching are both dramatically higher.

Smith, a low maintenance and non-confrontational person, did not want to make a big issue out of her injury, so she silently suffered through the discomfort at her swim practices. That all changed a few weeks later while she was sitting in her math class and began to feel the pain intensify, affecting her ability to breathe.

“It was almost like someone was stepping on my chest,” said Smith. “The pressure was so great that it literally stopped me from getting any air. Asthma had never caused those symptoms, so I was worried because I didn’t know what was wrong with me.”

Her teacher immediately sent her down to the clinic so that she could take her inhaler. When that had no affect on her breathing, she was rushed to the emergency room by ambulance. Once there, she was given some warm water to drink in an attempt to loosen the muscles surrounding her ribcage and some IVs to keep her hydrated.

The doctors at the hospital were not quite sure what had brought on the sudden attack. They ruled out her asthma, as the inhaler had no affect, and suggested that it could have been an anxiety attack or simply bad allergies. Feeling slightly uneasy without a concrete diagnosis, Smith left the hospital and hoped that the attack was simply an isolated incident.

One week later, Smith’s hopes were shattered when she had another breathing attack, this time in her P.E. class. Again, after her inhaler failed to cure her symptoms, she was taken to the hospital. Because it was the middle of October by this point and the allergy season was in full bloom, the doctors questioned her over possible allergies she may have. Up until that point, she had had no known allergies to anything. But, just to be on the safe side, her parents brought her to an allergist to get tested for anything and everything that could be the reason for the attacks. This visit proved fruitless when the full battery of tests revealed no new allergies.

The doctors took it one step further by asking that all of the classrooms that Smith had classes in be tested for mold. Mold has the potential to cause very severe reactions in people who are allergic to them. This theory, which had already been knocked down after Smith had no reaction to mold in the test, was further disproved when none of her classes had any trace of mold.

Her next attack occurred outside in her English trailer. Inside the ambulance, the paramedics gave her three puffs of Albuterol, the medicine found in fast acting inhalers, despite the fact that she had already taken two in the clinic. Because it was her second visit to the E.R. in a short time frame, the doctors at the hospital decided to take an X-ray of Smith’s chest. When they came back and showed no irregularities, the doctors began to look for alternative causes of her chest pain. Smith’s heart rate had been elevated when she had first entered the hospital, so the doctors recommended that she visit a cardiologist to be examined for any heart conditions.

“After the second hospital trip, I went to the cardiologist like they recommended. They did a stress test on me, to see how my heart reacted to physical activity,” said Smith. “They also performed a sonogram of my heart, which was pretty cool because I got to see it beating.”

Smith’s attitude was not quite as positive when both came back normal and, after three more visits, she left yet another doctor’s office without a diagnosis.

Roughly a week later, Smith and her parents visited a different doctor in the same building as the previous cardiologist. This doctor first suggested that Smith get an MRI test of her upper body, which would show any tears of irregularities in the soft tissue in her upper chest. When this test came back as completely normal, the doctor described Smith as an “anomaly.”

“That was awful!” said Smith. “I mean, he was supposed to be the doctor and he had absolutely no clue what was wrong with me or how to fix it.”

Caroline Gamble, Smith’s mother, had been doing a lot of research online to try and identify conditions with similar symptoms to her daughter. She came across a condition known as costrochondritis, where the cartilage of the upper chest becomes inflamed and causes chest pain. This diagnosis would explain why Smith was having chest pain, but still would not explain the sudden attacks she had been experiencing.

After living with chest pain for more than eight months, Smith and her family finally received the breakthrough they had desperately been searching for.

“My aunt called my mom and recommended a doctor that she knew of in Richmond who might be able to solve my problem,” said Smith. “I went down and saw him with my parents. He took a look at my past medical records, which took up a large file after all the doctors visits the previous year and gave me an examination.”

After relaying her entire story to him, her symptoms, feelings, and sudden breathing attacks, he was able to produce a diagnosis. Smith had a condition where her ribs would partially dislocate with strenuous activity. At the time her symptoms began, she had increased the number of swim practices she attended, which were already escalating in difficulty. The bad cough that she had had all throughout the fall could have brought on the sudden breathing attacks, because they further damaged the already sensitive tissue in her chest.

Although the diagnosis was not particularly positive, it was all Smith had hoped for her entire freshman year: an answer. By the end of that year she had stopped swimming completely because the pain had become unbearable. The Richmond physician instructed her to stop all physical activity for the time being to allow the cartilage that held her ribs in place to heal.

“I went to a physical therapist for a few months and learned some new exercises to help me repair my damaged muscles, but most forms of exercise are still really painful. I walk a lot and bike ride, but other than that I can’t really do too much.”

Now, two years after her initial diagnosis, Smith’s breathing attacks have completely stopped, along with most of her chest pain.

When asked how she felt about her ordeal in retrospect, she simply smiled and said, “I’m just glad it’s finally all over.”