“Your organization’s Internet use policy restricts access to this web page at this time.”

This message pops up on phones, iPods, and computers all over AHS, but students need only to type in a few extra symbols, like the added “s” in “https,” and they have access to the blocked content. No one seems to know why the administration sets up these barriers, especially when they are so easily navigated.

Although many students are frustrated, AHS filters the Internet because it is required to do so by federal law under the Children’s Internet Protection Act. FCPS is obligated to follow certain regulations since the county receives yearly funding through the E-rate program, which provides financial aid to libraries and K-12 schools in the United States. Schools that receive these benefits must have an Internet Safety Policy restricting websites that present inappropriate material. The policy censors content such as child pornography, material that encourages or teaches illegal or criminal activities, or any material considered harmful to minors.

The criteria seems reasonable; after all, students don’t need to be researching different ways to commit a felony during school. But FCPS filters some online content that doesn’t seem to fall under the category of “harmful to minors.”

Take YouTube, for example. Students can access YouTube, but what they can’t access is PSY’s Gangam Style or Taylor Swift’s music video for “We Are Never Ever Getting Back Together.” Even lyric videos for Carly Rae Jepsen’s “Call Me Maybe” bring the dreaded “blocked content” message.

“Filtering videos is absolutely incredulous,” sophomore Sabrina Rivera said. “[There are] videos [that are] specifically filtered, yet we have no problem watching videos such as ‘The Innocence of Islam,’ [which] attacks the beliefs of Islam, yet harmless music videos are blocked because they are mainstream and popular to my generation.”

However, the filtering program restricts content that may otherwise take students by surprise. Imagine you’re doing reasearch for a governement project. Researching the White House’s website sounds perfectly safe, right? Wrong: www.whitehouse.gov is safe, but other websites with the same domain (whitehouse) and a different top level domain (the .com, .org, or .gov) will take students to dangerous and inappropriate sites. Some websites have a URL that looks similar to a safe website, but the top level domain is different, and can take unsuspecting web users to an unsafe website. These websites would appear as blocked. “Teachers don’t want to be embarassed by accidently hitting a site [with inappropriate content],” school-based technology specialist Rebecca Bartelt said.

Even though some blocked material seems reasonable, there is still some censored content that seems unjustified. Students are quick to point fingers at AHS administration, but they may not be to blame. AHS doesn’t necessarily decide what is filtered and what isn’t. Most of the censoring is done centrally by DIT (the Department of Instructional Technology), outside of AHS’s control, but administration does have the option to request that specific pages be blocked or unblocked if they feel there is enough cause to do so.

To apply these restrictions, FCPS uses a program called WebSense, a security program that can filter a specific page (ex: www.website.com.discussion/arp.html), directory (ex: www.website.com.pics), website (ex: www.website.com/), or entire domain (ex: website.com). WebSense users with the proper authorization (like administrators) can view reports that include what websites have been blocked or visited, as well as the specific dates and times. The WebSense reports even allow users to view the IP address of the computer that accessed or attempted to access the websites.

Even with all the program’s benefits, students still find ways to access blocked content: “It’s easy, you just use H-T-T-P-S,” senior Omar Abdulrahim said.

HTTP is what typically appears in front of the “www.” in web addresses. It stands for “HyperText Transport Protocol.” HTTP is essentially a language that communicates information between the Internet user and your Internet provider. HTTPS is a little different. The S in HTTPS stands for “Secure.” Comparatively, HTTP is “unsecure,” and someone can potentially see any information you might put online. HTTPS is “secure,” meaning that no one should be able to spy on your personal information.

Atoms also use web programs to get around restrictions: “There’s a program on Firefox that lets you bypass the firewall,” senior Jose Cordero said.

Students seem to have mostly negative opinions about the filtering system, and the general consensus is that the FCPS censoring program is ineffective.

“There’s not really any benefit; they should just give up,” sophomore Ayobami Fakulujo said.

On the other hand, most teachers say that the filtering is necessary, and see it only as a minor inconvenience.

“If kids are going to access the school’s Internet, then the school has the right to monitor that,” history teacher Whitney Hardy said.

“The reason it’s there is to protect [the students],” Bartlet said.

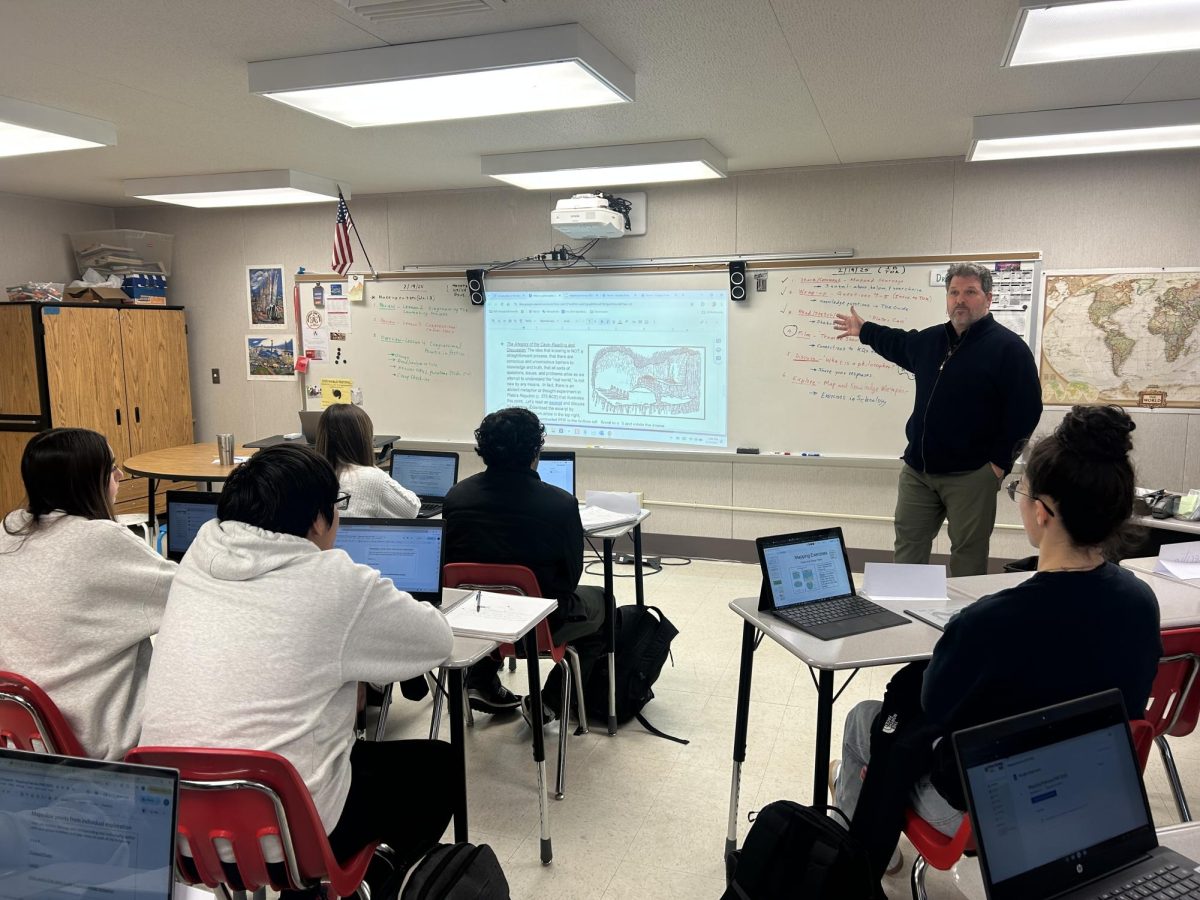

While necessary, the restrictions occasionally create roadblocks in the classroom with demonstrations, research, and projects.

“There are times when it’s kind of bizarre,” English teacher Cindy Sebring said. “A kid will be doing a project and a lot of the sites will be blocked. For some topics, it can be a little bit of a barrier.” Health classes may run into this problem, especially with research concerning drugs or family life education. Teachers have also encountered trouble reaching content when their education-based searches have keywords that are misinterpreted as unsafe by the computer.

“It seems inconsistent and sometimes gets in the way of things I want to show,” English teacher Joy Korones said.

Even with the occasional drawback, teachers seem to agree that the filtering system is both crucial and mostly functional.

“If it’s not academia, I don’t see why they’re watching it,” Sebring said. “[The FCPS] filtering system is good.”

Despite a few hiccups here and there, the general consensus is that the system is beneficial to AHS. Students may find it less than satisfactory, but many teachers and parents see it as a necessity, especially with all the potential for minors to access inappropriate websites and content during the day. The program may not be perfect, but it helps to keep kids’ attention off of their phones and focused on their education.