Based on its expenditures, the United States should have one of the best education systems in the world. We devote 17.1 percent of our yearly budget on education, or roughly $10,000 per student, while other developed countries, such as England, France and Spain, spend only a little more than 11 percent. Yet, according to the OECD Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), America lags behind such countries in almost every subject. Among thirty-four other developed countries, we rank 25th in Math, 17th in Science and 14th in Reading, trailing behind top scoring countries such as Finland, Canada and Japan.

These kinds of statistics are alarming for a country that was once a pioneer in public education. When the concept of public schools–the idea of free, compulsory education, paid for by taxation–emerged in the mid-1800s, it was revolutionary. It changed a society which, before the breakthrough, limited the privilege of schooling to the wealthy upper classes.

As prominent education and creativity expert Sir Ken Robinson and other scholars note, the motive behind the development of public education systems in America was primarily economic. Seeking to deal with an influx of immigrants to the U.S. and a growing number of unskilled laborers, leaders of the public education movement designed curricula in a way that would ensure basic literacy and provide factories with trained and competent workers. As a result, schools were designed like factory assembly lines. Even today, most public schools in America feature simplistic building plans separated by subject areas and religiously follow schedules of ringing bells; the same type of environment experienced by production laborers. Children are educated in batches, separated not on the basis of abilities or interests, but on their age. More often than not, schools view students with the same mentality with which factories view their products. The focus is less on individuality than conformity, or ensuring that each student emerges from their educational experience with roughly the same skills.

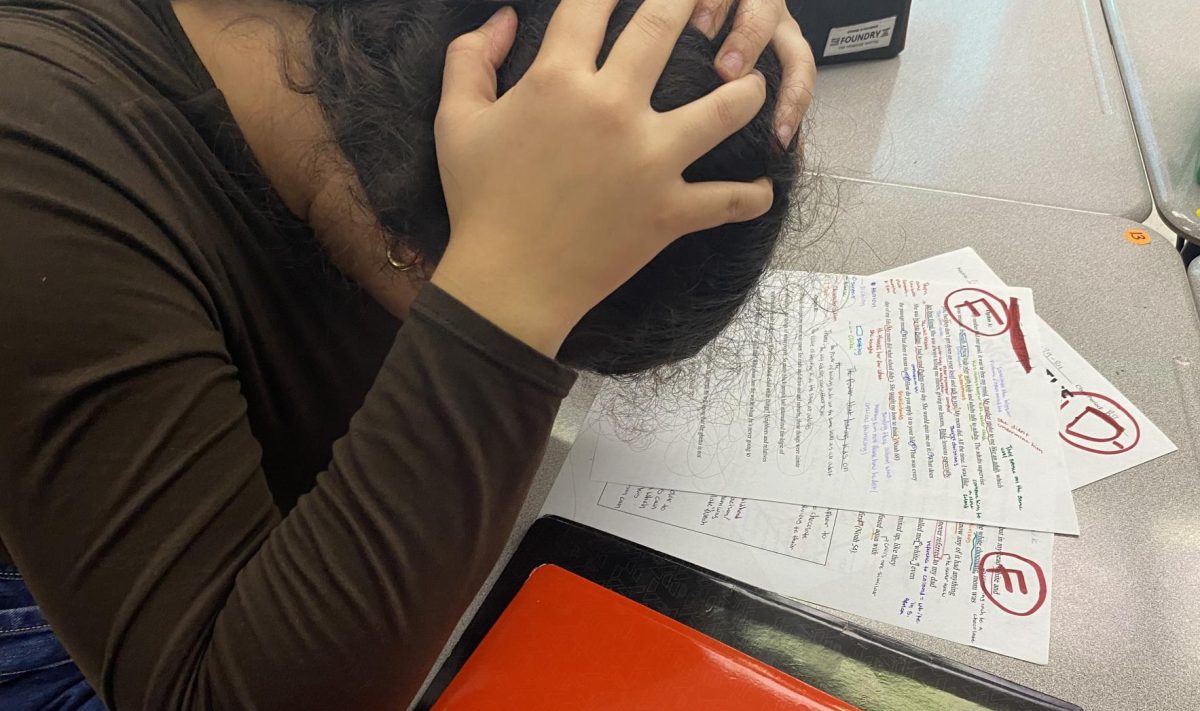

While this system was suited to the needs of the 1800s, it is no longer relevant. As the world rapidly grows more complex and globalized, creative and innovative thinkers become a much more valuable commodity than those trained to excel in an outdated system of education. Yet instead of changing to fit the needs of a rapidly changing world, U.S. school systems cling to old traditions and beliefs. Programs which encourage divergent thinking, such as the arts, are ruthlessly cut out of education budgets and replaced with more standardized testing, despite studies which show that participation in arts programs and creative teaching methods increases interest and performance in school subjects such as science, math and reading. Many schools also struggle to incorporate modern technology into their teaching methods despite its pivotal role in virtually all career fields. Though the lack of up-to-date technology in schools is often due to budgetary restrictions, many teachers fail to recognize the value of devices like laptops and iPhones, viewing them as distractions rather than creative tools.

The dedication of American public schools to the concept of conformity is clearly displayed through their dedication to standardized tests, which is supported by legislative action on the part of the government. The most recent and prominent piece of legislation concerning standardized tests is the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001, a major initiative of President George W. Bush. The Act established strict standards in reading and math which schools must meet in order to receive federal funding. This piece of legislation is the underlying reason for the SOL tests that AHS students experience each year. While the No Child Left Behind Act was established as an effort to reduce the number of fundamentally uneducated students emerging from U.S. high schools each year, it unconsciously enforced the notion of conformity and restricted the ability of teachers to develop more creative lesson plans. School budgets were quickly redirected away from creative programs and towards those that drilled students on the simplistic test requirements, simply in order to receive necessary federal funding.

The 2001 No Child Left Behind Act, and standardized testing in general, are still greatly contested among educators. The advocates of such methods of measuring performance, usually known as “back to basics” educators, support the notion of standardized curriculums, claiming that it ensures that all students possess at least a basic level of academic skill. The opponents of standardized testing, or “progressives,” view intellectual freedom as the cornerstone of democratic society and view student autonomy, creativity and curiosity as the most prominent aspects of a meaningful education. By forcing schools to view conformity as a desirable goal, they argue, standardized tests alienate millions of students by limiting their natural ingenuity and turning them against education.

Many excuses are made for America’s poor international rankings in education and our troublingly low math and science scores, which are equivalent to those of students in Third World countries like Thailand and Serbia. Some educators claim that PISA rankings are unfair because other countries select their top-ranking students while the U.S. tests all of its eligible public school attendees. Others claim that the high number of immigrants in public schools drags down test results. But as other nations begin to test greater numbers of students and new studies reveal that even upper/middle class pupils with at least one college educated parent earn mediocre results on standardized tests, such excuses begin to fall flat. The American public education system should be one of our greatest assets and sources of national pride. Instead, it has gained a reputation as a failure, which ultimately produces lackluster and unenthusiastic students. Many argue that U.S. schools fail their students, and thus ruin the creativity of generations of children.