Activism transformed

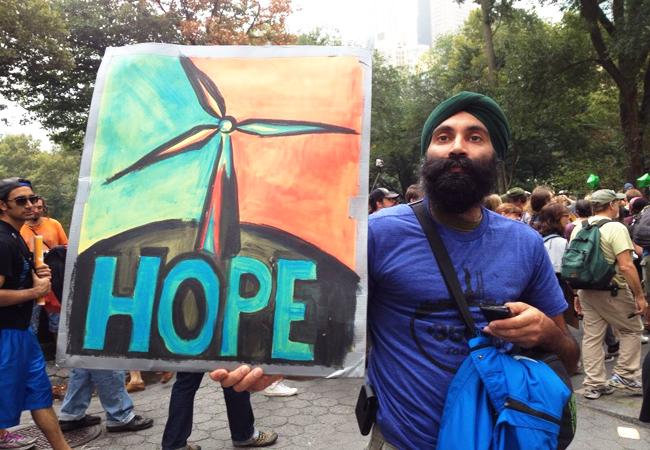

This protester marched in the People’s Climate March in NYC this September.

Since the start of the millenium, a craze has swept the globe. It eats up our hours and shapes our lives, molding the youth who will become future leaders. Social activism has made a comeback.

“The American Civil Rights Movement was very much a part of my generation. I went to Washington for the famous march,” social studies teacher John Hawes said. “The Washington rally was peaceful, successful and there was a lot of spirit that said ‘activism can work.””

Activism was a large part of Hawes’s youth. Graduating from high school in 1959, he spent his years as a young adult surrounded by the multitude of social movements that came out of the 1960s. His sister was a Freedom Rider, riding integrated buses all through the South to protest segregation and discrimination.

“Activism has not had nearly the same success anywhere since,” Hawes said of the American Civil Rights Movement.

Most of today’s social activism can, in some way, fit into the category of internet activism. In today’s fast-paced world, it’s just more practical for social justice organizations to communicate with followers online. The Internet has drastically changed the way information is spread.

Gone are the days of traipsing around town, stapling brightly colored flyers to wooden posts in the hopes that someone will take notice. Today we have mass email communication, Facebook groups and online petitions to spread the word about our concerns.

“[Tweeting] doesn’t cost you anything intellectually, emotionally or physically,” Hawes points out. “The people in the Civil Rights Movement were actually putting their lives on the line and doing jail time.”

Even though most of us aren’t diehard activists, the easiest thing you can do also happens to be the most important: stay informed and have opinions. Coincidentally, that’s also the most important part of being a citizen of a democratic nation.

It’s embarrassing that only 36 percent of Americans can name all three branches of government. That’s according to a poll conducted by the Annenberg Public Policy Center on Sept. 17 of this year. That was the same day America celebrated national Constitution Day, commemorating the 227th anniversary of the signing of the Constitution.

There’s really no excuse for ignorance when we are constantly being bombarded by social media alerts and news updates. We’ve been pampered by this plethora of information for most of our lives, relying on the instant-gratification of the Internet to do our homework, talk with friends and watch our favorite shows.

This transformation in our lifestyle is a relatively recent development. In 2000, the Internet held over 51 percent of the information in all telecommunications networks, up from only one percent in 1993. In two decades, we went from living in isolated nations to existing as a global community in an interconnected world, united under binary code.

With Internet obsession changing the way we interact, we must ask the question: are we actually participating more in society? Does the rise of Internet activism automatically equate to a more informed and passionate populace?

“Technology is very successful in drawing people in,” Hawes said. “However, it may not be connected with enough of the people who actually care deeply enough to do something.”

The term “slacktivism” was coined by law professor Cass Sunstein to describe the activity of supporting a cause in a way that doesn’t make a real impact. People do this to feel good about themselves and give their online persona the appearance of being a conscientious citizen.

An example of “slacktivism” would be retweeting a statement or joining a Facebook group about saving the whales and then promptly forgetting about it. You might say to yourself, “I’m such a good person, now everyone will know I care about marine life!”

I’m not condemning all the “slacktivists” out there, because in the past I’ve been one myself. It’s not ideal, but it’s better than remaining ignorant and doing nothing.

It’s surprising how the number of Facebook likes can contribute to the success of a movement. People will decide to attend a march or legislators might decide to act on a cause based on these arbitrary numbers.

“Activism is an important part of solving a legal issue,” Hawes said. “The Civil Rights Movement had the benefit of having a very specific and genuine target.””

For leaders to take an activist seriously, their movement has to have a purpose. If their issue is considered vague or unimportant, law-makers will disregard it and move on to one of the hundreds of other complaints they have to deal with.

“There was a general sense that the people in power were wooden and needed to be moved,” Hawes said.

If you’re a serious political activist, it might be important to remember that legislators act as puppets. After all, congressmen work for us. It’s their job to listen to our complaints and suggestions. It’s just a matter of garnering support for your cause and presenting your movement in a professional and organized manner.

“The depth of commitment and organization it takes to change a society is humongous,” Hawes said.

Just like in the 1960s, movements are popping up all over the globe. The Arab Spring pro-democracy movements that started in 2010 are still going on, as well as similar movements in Hong Kong, DR Congo, Darfur and several other locations.

The Climate Change, Gender Equality and Gay Rights Movements, just to name a few, are huge campaigns with millions of followers spread around the globe.

“Activism was not just in this country, but it was a global contagion,” Hawes said. “Even before the Internet and Twitter, people paid attention.”

Hawes makes an important point. To recreate the success of the Civil Rights Movement we need to pay attention to the real world, not just selected parts of the worldwide web. Activism needs to be infectious, permeating our lives and prompting us not only to click, but to act.

Sarah Metzel is the current Editorals Editor of The A-Blast. She joined the staff sophomore year as a staff writer.

Metzel was accepted into the Young...