By Gwen Levey, Arts Editor

They’re science’s artistic wonder, panning out from the world around us and playing tricks on our peripheral vision. They come in many different forms, shapes, and sizes, while ultimately managing to maintain their invisibility to our naked eye. They are always there and are typically associated with the visual art curriculum, but if you walk into a science classroom at AHS, you might be surprised at how they have increasingly become part of the curriculum there as well.

“When I taught the nervous system last year I showed a powerpoint tying optical illusions into how our peripheral vision tricks us,” biology teacher Rachel Lazar said. “The students really loved it and I think it even helped them understand the material more, so I’m going to show it again when I teach the unit this year.”

Geo-systems teacher Jill Rasmussen also agrees that optical illusions have helped to make covering the nature of science to her students more beneficial. “By showing examples of optical illusions in class, the students begin to realize that we as human beings have different perspectives and when we share those perspectives with each other, we learn that the world as a whole is bigger than just its parts,” she said.

Students also agree that relating optical illusions to what they are learning in science is highly beneficial to the way they understand the material, though some walk into their science classrooms without realizing that the two subjects relate.

“I never realized that optical illusions would apply to my physics class until we learned that the movement of particles help to deceive the eye and cause the illusions,” junior Mairead Kennedy said.

Like at AHS, the founding of optical illusions are somewhat new to the science world themselves, even though they’ve existed since the beginning of time. It would be many years into the creation of the world before more scientists actually began proving these theories and the idea of optical illusions would become popular, leading up to famous visual illusions in music, jobs, nature, and most notably, visual arts.

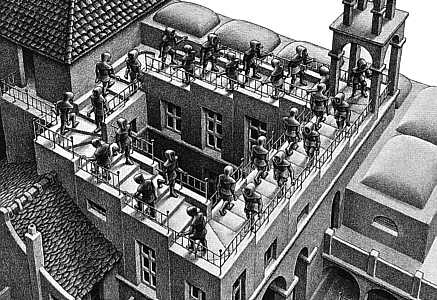

“Once students see the examples I show of these optical illusions, such as M.C. Escher’s work, they immediately know what I’m talking about and will even tell me of others that they have seen,” Lazar said.

Spanning out from just the world of science, if you travel down to the history hallway of AHS, one might find how the teaching of optical illusions has also existed throughout history.

“I never knew that simple architecture from ancient cultures, such as the Greek, used forms of optical illusions,” sophomore Dominic Maier said. “It’s weird that a lot of the time that I was sitting in my world history class, I was also learning about some of the history of optical illusions too.”

In modern times, one of the most notable optical illusions that AHS teens, parents, and teachers use everyday is the television. If it’s hard to believe, think of the jarring fact that the pictures aren’t really moving when you watch it, but only the speed of the pictures are, since one’s brain cannot take in every single picture, which is really just made up of tiny little dots of color anyway.

“The ability to interpret makes us unique as organisms, setting us apart from others in this world,” Lazar said. “Just like with optical illusions, we use our experiences as a lens for what we’re seeing, which is why they’re a nice add to teaching.”